Can anyone actually monetize OpenClaw?

OpenClaw might be the fastest-growing open-source project in history. 145,000+ GitHub stars in two months. Millions of users.

Its creator, Peter Steinberger, probably has an inbox full of VCs offering money. Yet he has been crystal clear: “It’s a free, open source hobby project.”

But no AI technology this popular escapes monetization. The question isn’t whether somebody will try—that’s already happening (with hosted options like Molty). The question is whether there’s a sustainable business to be built.

Because OpenClaw has become the ultimate stress test for AI pricing and monetization. It exposes why monetizing AI products is so hard and why you might not be able to offer all the features you could build.

If you’re building anything with AI, you probably know this dilemma: There’s a dream use case, a feature you know is possible, but would consume too many tokens to be economical. OpenClaw just makes it impossible to ignore.

What OpenClaw Actually Does

OpenClaw is a computer-use AI agent. Imagine if an LLM could do anything you can do on a computer. It clicks, types, browses the web, operates apps, calls APIs and uses the terminal. It stores everything in persistent memory to learn your habits and preferences.

Steinberger has used it to monitor security cameras, control his smart home, and get restaurant recommendations via WhatsApp. These sound like the types of neat things a hacker might build in their free time. But Peter Steinberger knew he’d built something special when his agent did something he never programmed it to do, something he expected his agent to fail at: He sent a voice message with instructions via WhatsApp.

The agent realized it didn’t get the file heading, found local converter tools to turn it into a more common format, located an OpenAI API key and used it to transcribe the audio, ingest the text as a prompt and then taking action on the instructions.

OpenClaw is what Siri and Alexa promised to be. A fully autonomous AI assistant, the thing the big labs wish they could ship but don’t.

With installation being super difficult for anyone but serious engineers and requiring various API keys, integrations and LLM connections, it feels like the perfect startup opportunity: Make an extremely capable, but technically difficult technology more accessible.

Yet as of now, it’s going to be extremely hard for two reasons: Because it’s a security nightmare and too expensive to run.

Security is outside the scope of this article, but you can imagine that giving AI access to your entire file system, API keys, social media accounts and (as some users do) even credit cards creates vulnerabilities (to say the least) and makes it unsuitable for any work tasks that involve customer data.

Since we’re talking about monetization and pricing, let’s look more into the second part: Cost.

The Core Problem: Unpredictable Costs, Questionable Value

OpenClaw can run on basically any LLM. But whether you use the expensive Claude Opus (Anthropic’s flagship model) or a more economical open-source model by Mistral, OpenClaw consumes a ton of tokens. And people are aware of this:

AI consultant Shelly Palmer spent $250 on setup alone. There seems to be no way to use OpenClaw without spending hundreds a month for anything resembling normal usage. In that range, you could get Claude Max and ChatGPT Pro while treating yourself to a Cursor seat.

So when you can’t use it for work (where it would have the highest ROI), and it costs hundreds of dollars in tokens alone to operate something normally, who would be willing to pay the price?

Whenever you try to price anything, you need to answer two questions:

What is the value I’m charging for?

What does it cost me to serve the product?

These have an interesting relationship: The more it costs to serve the product, the more you need to charge. The more you want to charge, the more value you need to offer. So we already know OpenClaw is expensive. And if you built a company on top of it, the salaries, infrastructure and other costs would require you to charge thousands a month!

But is the value commensurate? Brandon Wang wrote about his OpenClaw workflows: tracking freezer inventory via photos, managing grocery lists from recipe screenshots, auto-booking restaurant reservations by logging into Resy and cross-referencing calendars, entering 2FA codes, to log in. Peter Steinberger himself mentioned that it checks him into flights and makes restaurant recommendations directly in WhatsApp.

These are cool. It’s impressive that AI can do it. But would you pay hundreds a month plus the headache of maintenance? Thousands through a commercial vendor? Probably not.

Of course, OpenClaw can do much more. But the high-ROI use cases of automating your work are also the contexts where letting an LLM run wild is a bad idea.

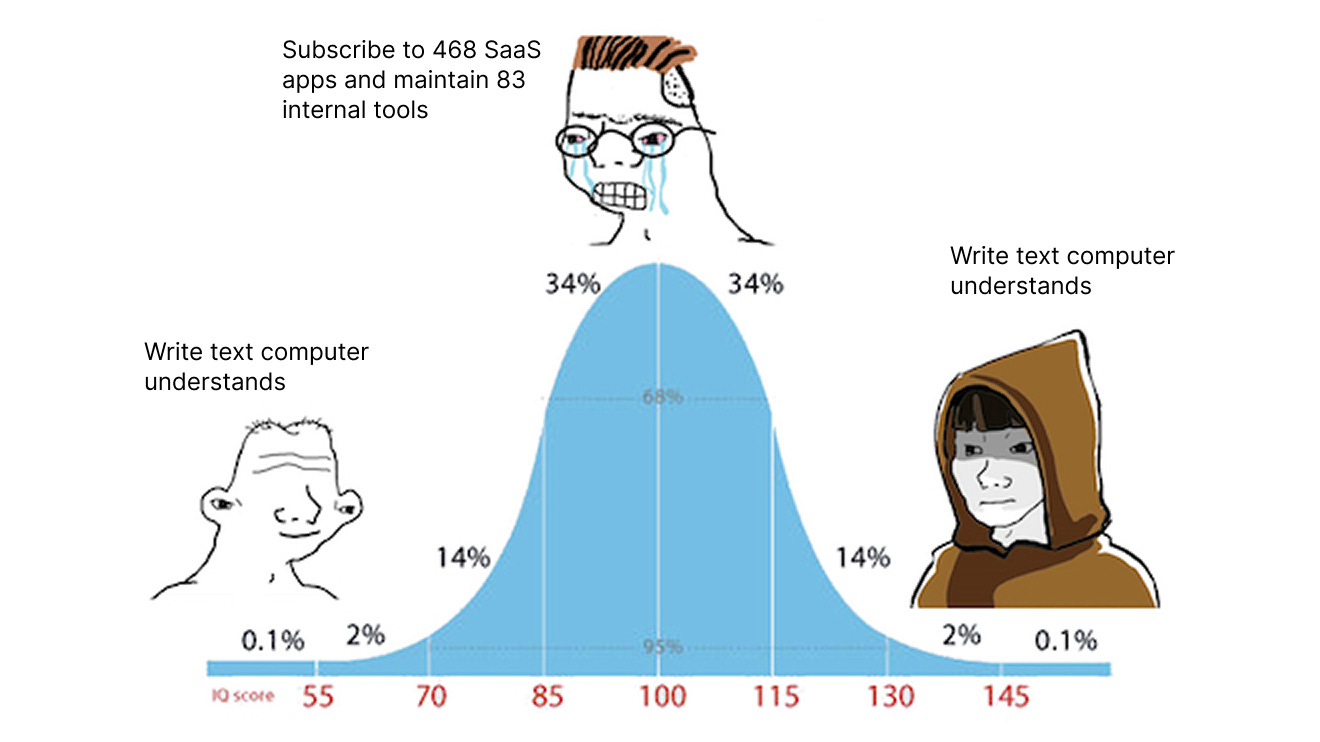

Of course, AI usage being expensive is not a new problem. Most AI companies like Lovable, Cursor, Replit etc. make their products accessible by limiting usage via credits or API budgets (after which you can top up credits or pay overages).

Yet this would be hard to implement for OpenClaw. To get the subscription price low enough to be acceptable to end users, the included usage would be so tiny the product would fail at its promise of being nearly omnipotent and always-on.

Other pricing strategies would fail too:

Cost-plus pricing (marking up AI costs 30–50%) fails because the costs would be even more massive than pure usage-based.

Bring your own key pricing (you pay a flat subscription and foot your own API bill) only works if someone’s willing to pay the hundreds a month in API costs.

Outcome-based pricing is hard to implement because the outcomes of a general-purpose AI agent are impossible to define. What should the price for an outcome be when one outcome costs $2 in tokens to tell the weather while another costs $200 to build new software?

So when ROI is low (freezer management, etc.) and cost to serve is high, is there any business to be built?

How OpenClaw Is Already Being Monetized

Founders are working on resolving some of OpenClaw’s headaches. Y Combinator’s Winter 2026 batch includes at least nine startups building on the technology. Bits’ Klaus offers “fast and safe OpenClaw on the cloud” with pre-installed security features. A number of startups including Simpleclaw, Runclaw, Clawdhost etc. offer hosted OpenClaw instances that help users skip the installation, basic integrations and provide basic guardrails.

These reduce the friction of using OpenClaw, but they don’t solve the fundamental problems. The underlying costs are still astronomical. Security is still a challenge (especially if you want to connect to work apps). You’re still consuming millions of tokens for relatively mundane use cases.

Building a business on OpenClaw probably requires constraining the technology into something with predictable costs and measurable value.

The only thing that could work? Selective Monetization

The key to monetizing OpenClaw is to not monetize OpenClaw. It’s to build constrained, vertical products that use OpenClaw under the hood to normalize token consumption and engineer those use cases to consume less. This makes consumption more predictable and easier to use common pricing schemes like credit-based subscriptions.

This pattern has worked repeatedly in open source:

FFmpeg → Cloudinary and Mux. FFmpeg can transcode, compress, filter, stream and manipulate video. But Cloudinary didn’t build “run any FFmpeg command.” They built an API that auto-optimizes delivery with a few parameters.

Kubernetes → GKE, EKS, AKS. Kubernetes can orchestrate any containerized workload across any infrastructure. But providers don’t sell “deploy anything anywhere.” They sell specific, opinionated patterns with guardrails, monitoring and scaling built in.

PostgreSQL → Supabase, Neon, PlanetScale. Postgres can do anything a relational database can do. These companies commercialized it by constraining to specific use cases: real-time subscriptions, serverless scaling, horizontal sharding.

Successful commercialization often means reducing capability, not exposing all of it. This minimizes the security risks and simplifies the go-to-market. This makes security easier (because you don’t integrate with literally everything, but select tools that you can control).

Most importantly for OpenClaw, it unlocks B2B use cases. And if anyone can pay hundreds to thousands a month for an AI agent, it’s businesses.

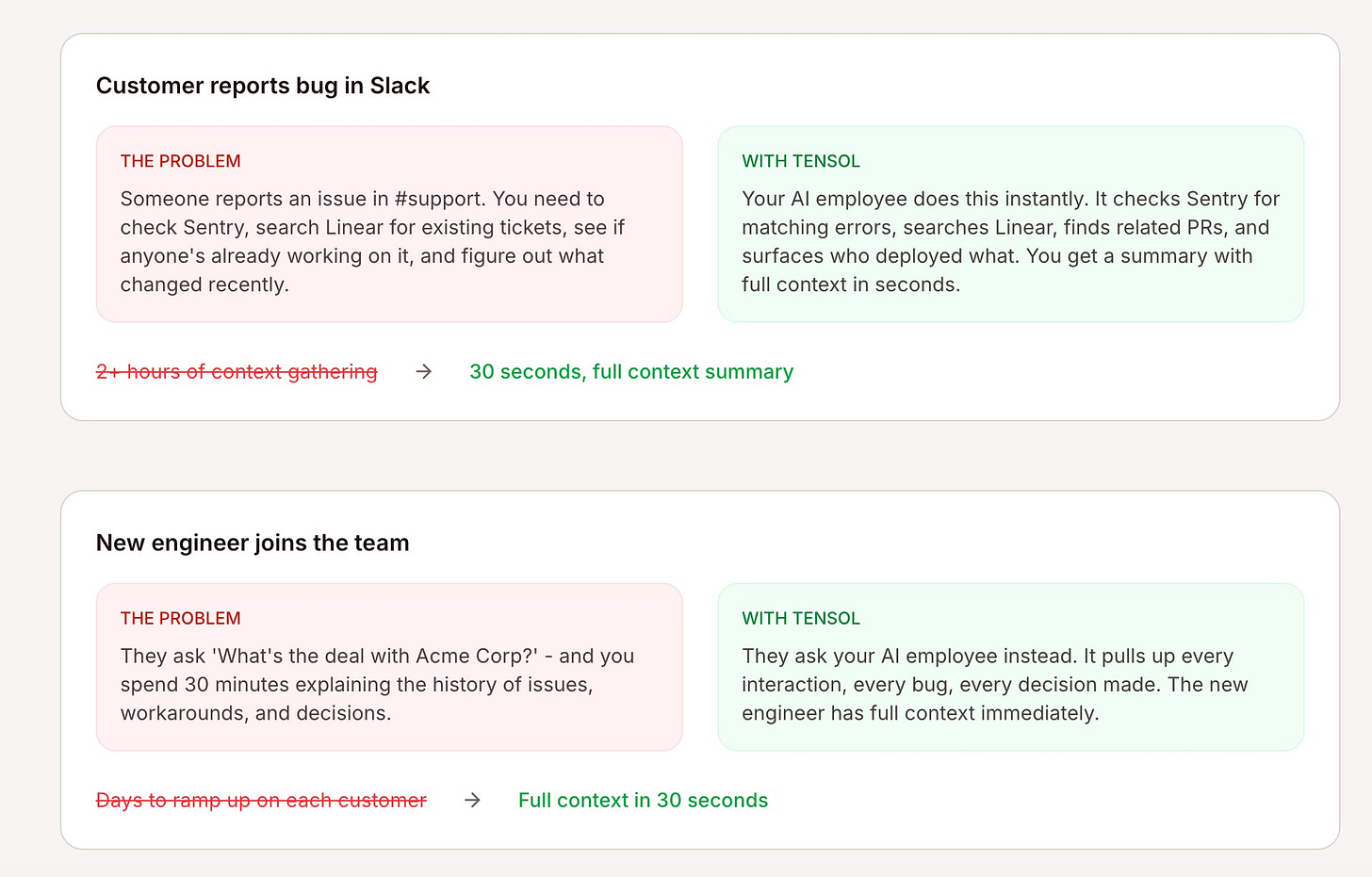

A great example of this is Tensol, another company from Y Combinator’s W26 batch. They offer “AI employees” (which now sound a lot more credible than the flood of crude AI employees of a few years ago).

This looks like a reasonable B2B use of OpenClaw. The use cases are specific to a workflow, which gives the agent good boundaries, both in the tools they can use (it won’t find a Twilio API key and call your customer at 2am to inform them a bug is fixed) and the boundaries it might overstep (it won’t use the context to post about the fixed bug on your LinkedIn).

This solves two monetization challenges:

It clarifies value to customers by applying the technology to a specific workflow customers are already running. This means it’s much easier to communicate what customers are paying for.

It makes cost more predictable by making the token consumption across different options more uniform.

Maybe the commercial opportunity isn’t “OpenClaw as a general-purpose agent”. It could be a hundred vertical products, each solving a specific expensive problem, each priced for the value it delivers.

But what if OpenClaw isn’t built for that?

Will 80% of Apps Disappear?

In his YC fireside chat, Steinberger made a bold claim: 80% of apps could go away once AI agents like OpenClaw become ubiquitous.

(For a moment, let’s assume the install friction, cost issues and security risks go away.)

He uses MyFitnessPal as an example. It tracks calories, suggests meals, logs workouts. It helps millions of people get and stay healthy and earns hundreds of millions in revenue for it. But it pales in comparison to what an OpenClaw-powered health agent could do.

An AI agent with universal data access could enrich this information with Apple Health data, cross-reference resting heart rate trends, scold you for the 2am KFC transaction it spotted in your bank account. It could proactively suggest quick HIIT workouts when you’re spending more time at the office and don’t have time for 90 minute workouts. It could tell you about frozen yoghurt places in your area when you’re eating lots of ice cream.

You can apply this to almost any app category. Imagine a productivity agent that reads all of your work and personal messages to keep track and remind you of everything without manual task management.

So when AI can do all of that, do apps just collapse into a chat interface? Does all of SaaS go away? Are we going back to early computing, when every computer interaction meant writing in a command-line interface?

It’s tempting to believe this. And commoditized apps might go away.

But people don’t use apps only for their features. OpenClaw’s chat interface can’t replicate Strava’s friendly competition, the tranquil typing experience of iA Writer or Notion’s smart thinking about primitives.

An impressive technology doesn’t equal a great product people will pay for.

Is OpenClaw just early?

OpenClaw is impressive. It reveals what LLMs can do when you give them almost no constraints and stop worrying about safety and cost. But I sense that OpenClaw is like a Formula 1 car.

Formula 1 cars are often built by ordinary car brands like Mercedes and Audi. Those brands are able to create cars that drive 350+ km/h. But those cars are not their products. On the road, an F1 car would have massive security concerns, cost more in gas than you pay for rent and have no space for passengers or luggage. A normal Mercedes doesn’t drive at those speeds because safer, slower, more economical cars are much better products.

Of course, the analogy breaks down at some point: A car requires real-world materials and keeps consuming gas. The costs of those fluctuate, but they don’t plummet. Technology does get cheaper over time. In the 90s, spinning up a (by today’s standards horrible) database required dedicated hardware, employees and a huge budget. Now Supabase gets you a full backend for free, by pushing a button.

AI agents like OpenClaw might experience the same. If token costs plummet the way database usage has, universal AI agents may go mainstream.

Most likely though, OpenClaw will be a technology powering products, not a product in and of itself. And that means constraining capabilities, defining use cases, measuring outcomes, building pricing that customers understand.

The winners of technologies are typically the ones who figure out how to package capability into a product customers find easy to buy because they understand its value and agree with its pricing.

The business opportunity isn’t in selling the equivalent of an F1 car to commuters. It’s in taking what you learn from F1 and building the car that actually fits someone’s life.

OpenClaw proved the technology works. Now someone has to build the products.