Why every AI coding tool gets pricing wrong

Nobody wants to have to apologize like Cursor did in July. From “Clarifying our pricing”:

“Our recent pricing changes for individual plans were not communicated clearly, and we take full responsibility. We work hard to build tools you can trust, and these changes hurt that trust.”

Ouch. You can imagine the panicked Slack messages, coffee makers running at 2am and the finance team’s despair at another quarter of unsustainable pricing.

Ever since AI made every user interaction cost money, pricing has become hard. Companies feel the squeeze of unit economics and have to devise complex pricing schemes. Customers are frustrated with usage limits and complex pricing.

Customers want unlimited usage, but companies can’t offer it without going bankrupt.

That’s especially true for one of the most token-intensive AI use cases: AI coding tools.

Whether it’s Copilot, Cursor, Windsurf or anyone else—users are eternally unhappy with pricing while companies still struggle with margins. And it doesn’t seem like things are improving.

Why AI gets more expensive, not cheaper

A few years ago, everyone assumed AI prices would crater so we could run the VC-funded startup playbook. Companies like Cursor assumed they’d burn money for a while before costs declined, 80% margins returned and we’d ride off into the sunset acquisition.

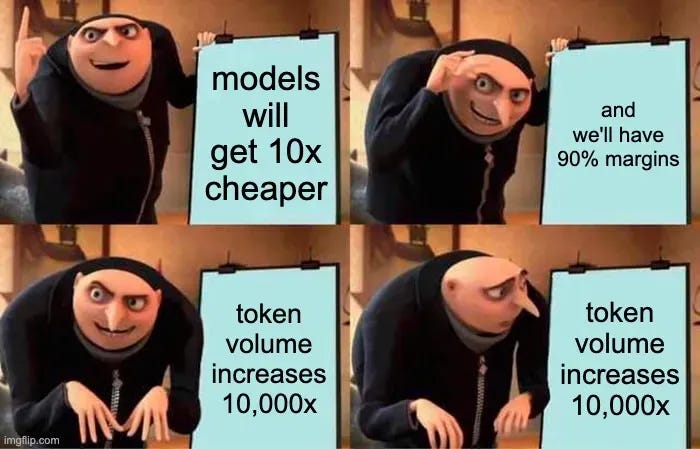

Then models became more expensive instead. Sure, GPT 3.5 is cheap now. But that’s like saying the iPhone 6 is cheap now. State of the art models are more expensive. And, as founder & CEO of TextQL Ethan Ding points out, also consume far more tokens (Ethan’s capitalization):

“i keep seeing founders point to the “models will be 10x cheaper next year!” like it’s a life raft. sure. and your users will expect 20x more from them. the goalpost is sprinting away from you.

remember windsurf? they couldn’t figure out a way to maneuver out bc of the pressure that cursor put on their p&l. even anthropic with the most vertically integrated application layer on the planet can’t make a flat subscription with unlimited usage work.”

He summarized it well in this meme:

It now looks like hope for cheap state-of-the-art AI has gotten so low that Cursor now trains their own models to not pay Anthropic’s margins.

Even companies with billions in funding, hypergrowth and world-class talent are trying everything to make the math work. Pricing expert Madhavan Ramanujam said on Lenny’s podcast that most AI coding startups undercharge: “The winners in AI will need to master monetization from day one. If you’re bringing a lot of value to the table and you started training your customers to expect $20 a month and you anchored yourself on a low price point, you’re in trouble.”

Whatever model you use—usage-based, credits, outcomes, subscriptions, overages—there’s one constant. Customers now pay for usage, not access.

Intercom founder and CEO Eoghan McCabe put it well: “For as long as these LLM services are so expensive, it’s going to be really hard for people to sell in a way that’s divorced from any kind of usage metric.”

Monetizing AI SaaS products is hard. And it’s even harder when your product is something users use all day and keep creating more costs. That’s exactly the spot AI IDEs are in.

In this article, we’ll walk you through why pricing AI coding tools is so hard and how to get it right the first time. Let’s start with the principles.

The 3 jobs of good pricing

Good AI pricing needs to accomplish three core things.

Maintain your margins

AI gross margins are lower (because AI is expensive) and volatile (because API prices and usage patterns change): The Information reported that Replit’s margins have varied between -14% and 36% in 2025 alone. Kyle Poyar, writer of Growth Unhinged and one of the loudest voices on AI pricing, put it this way: “And avoid flat fees or seat-based pricing unless you have the margins to support them.”

This means you need to understand how many tokens typical interactions cost and how big the swing between interactions are.

The latter one is needed because queries vary in token consumption. “Change this CSS class” consumes few tokens. “Build feature flags from scratch and integrate with Amplitude” consumes a lot. This is why Cursor switched to dollar-based usage budgets from an allowance of requests.

Pricing’s first job is maintaining margins. Cursor’s old pricing didn’t do that.

Be easy to buy

Pricing affects customer experience: If Netflix billed you by minutes of watch time, it’d be annoying even if you paid less. You couldn’t fall asleep in front of it, would worry about watching long movies, etc.

Nobody enjoys checking credit balance, monitoring token consumption or running into usage limits.

You need to price in a way your customers buy.

This affects what pricing strategies work. A rank-and-file employee with a corporate card could make a $20/month decision, but would need finance approval to commit to an unknown usage-based spend.

Elena Verna (Head of Growth at Lovable and ex-Amplitude and ex-Dropbox) once said: “Price has to be less than perceived value minus friction.”

For that rank-and-file employee, the friction of asking finance for approval for some unknown amount would be super high. For that persona, credits make sense because the card will never be charged more than the fixed subscription amount.

Keep you competitive

Pricing depends on your competition. There are two ways competition affects your pricing:

First, you can’t sell the same product at twice the price for very long. If you want to charge more than a competitor, you need to justify the premium. If you want to charge less, you need an operating model that lets you capture margins at low prices.

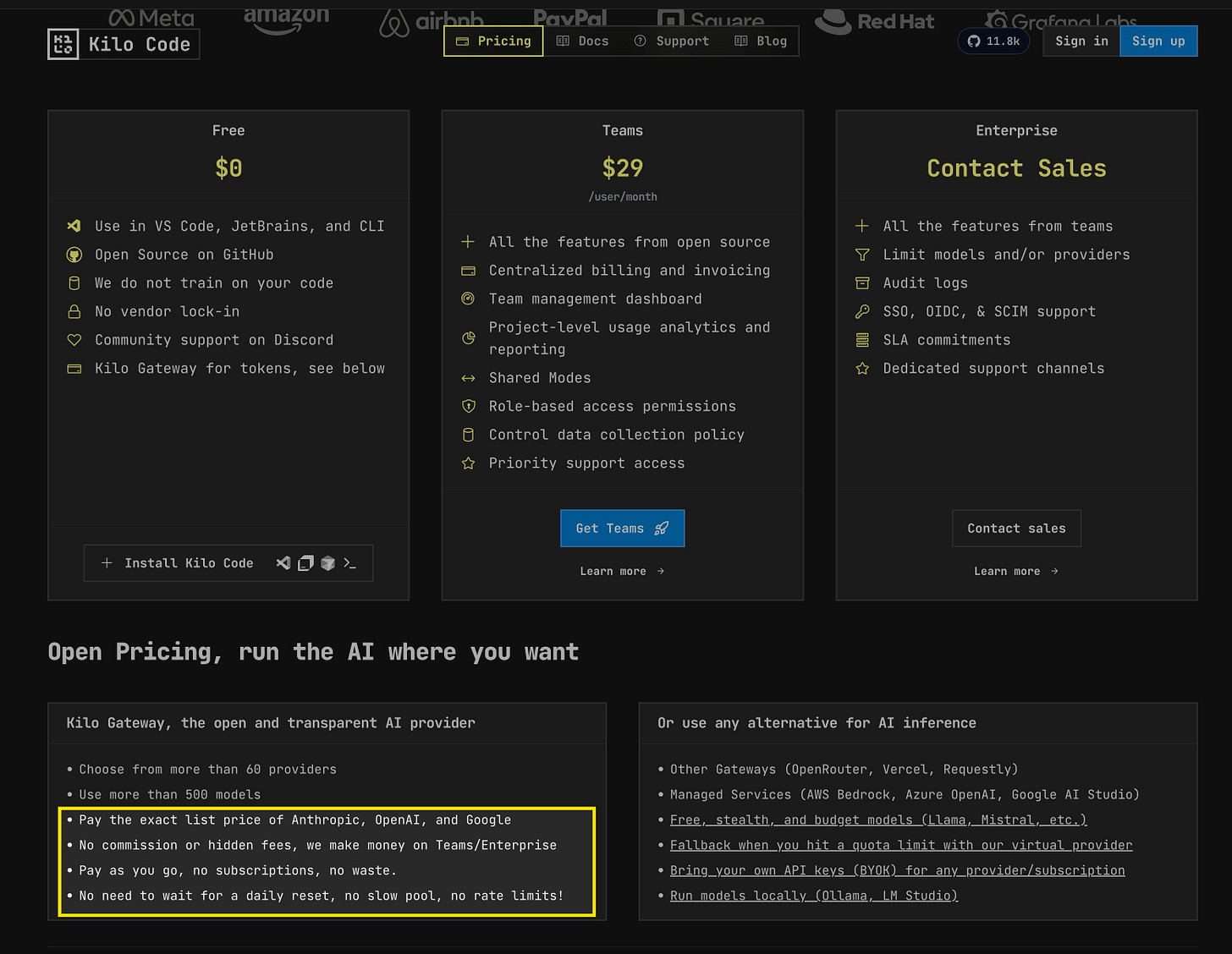

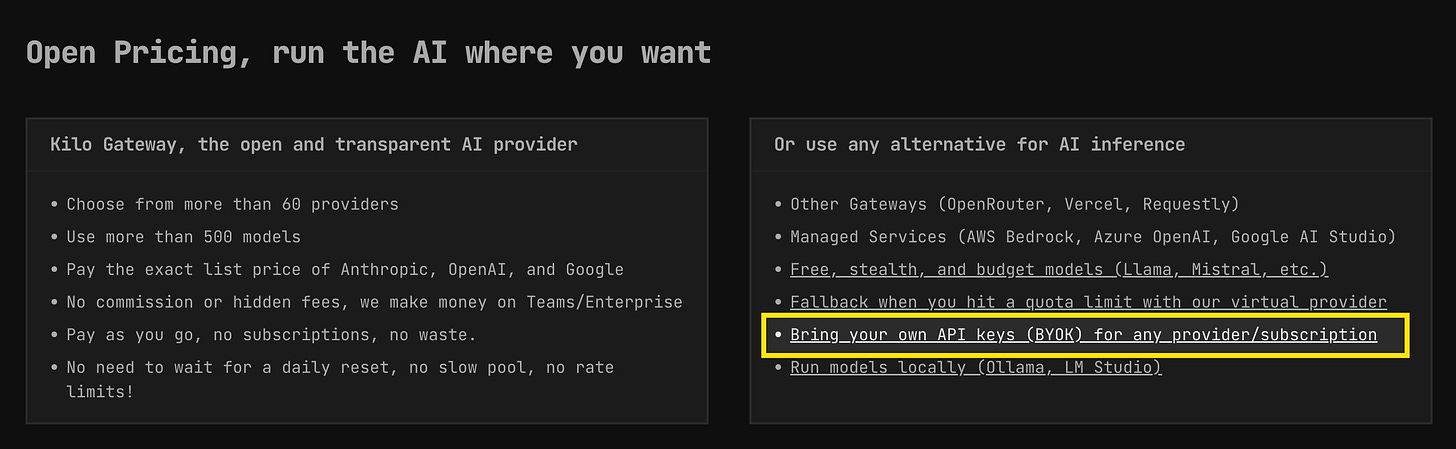

Second, some companies differentiate by pricing model. Take AI coding startup Kilo Code:

Kilo Code doesn’t differentiate on features, but on business model. Once a product category is large enough, some users will dislike the common pricing models and be delighted by something else.

This may sound easy, but the usage-based components required for pricing AI make it complex. Charge for pure usage and users will lambast the lack of predictability. Bill for credits and users will complain about paying for credits they didn’t use.

No pricing strategy is perfect. So let’s look at the most common AI IDE pricing strategies and where they (don’t) work.

AI coding agents, pricing strategies and where they (don’t) work

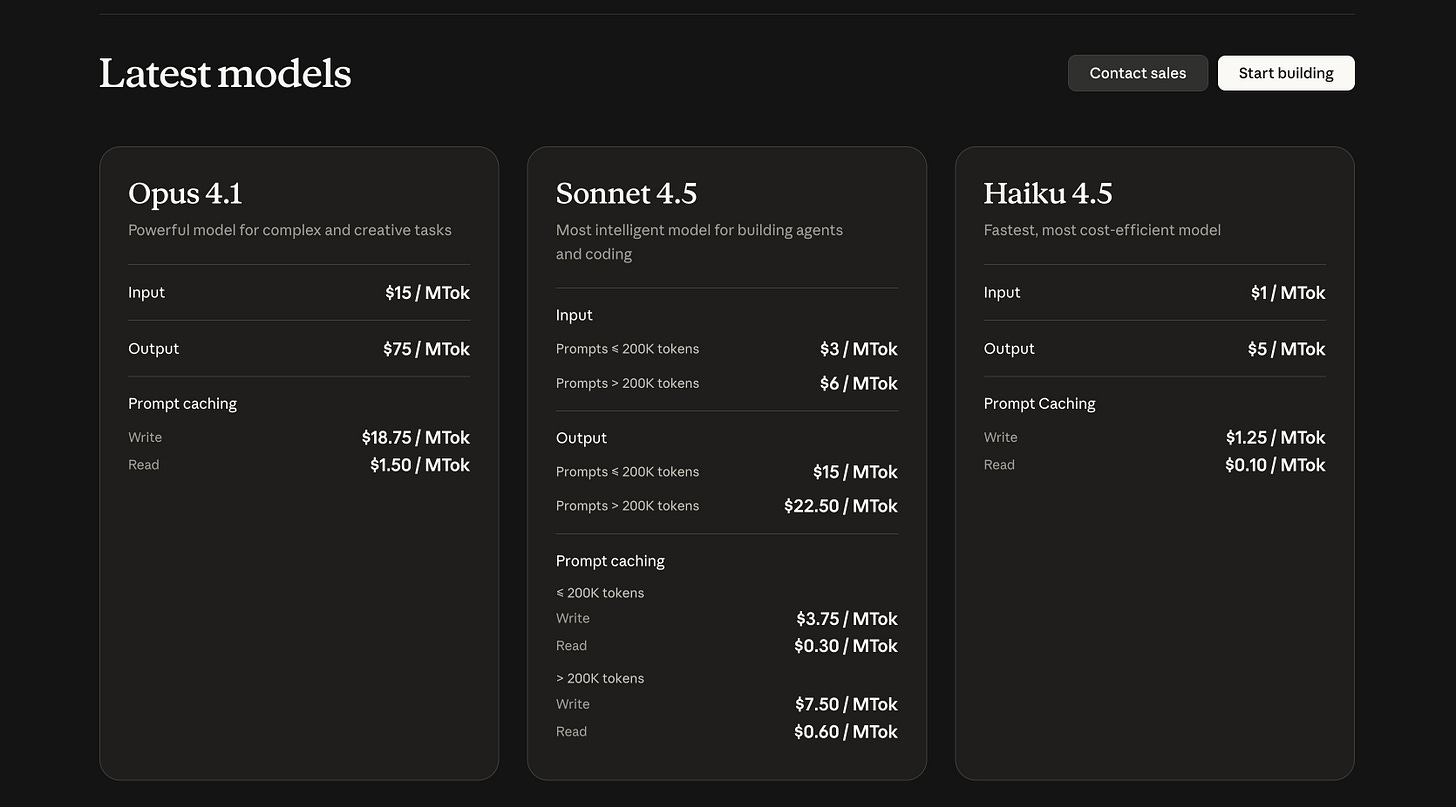

1. Pay-per-use pricing: Claude API

The “purest” usage-based pricing is to charge for consumption. This is what Claude API pricing looks like:

Customers only pay their exact usage. This works best for infrastructure because it’s an ingredient to another product.

Benefits of consumption-based pricing

Transparency: Customers never pay for anything they don’t use.

Guaranteed margins: You can calculate your costs and simply add margin.

Revenue expansion: If a customer’s business grows, so does yours.

Downsides of consumption-based pricing

Hard to monitor: Someone needs to monitor spending.

Difficult forecasting: Revenue is not recurring, so it’s harder to forecast.

Revenue contraction: If a customer’s business shrinks, so does yours.

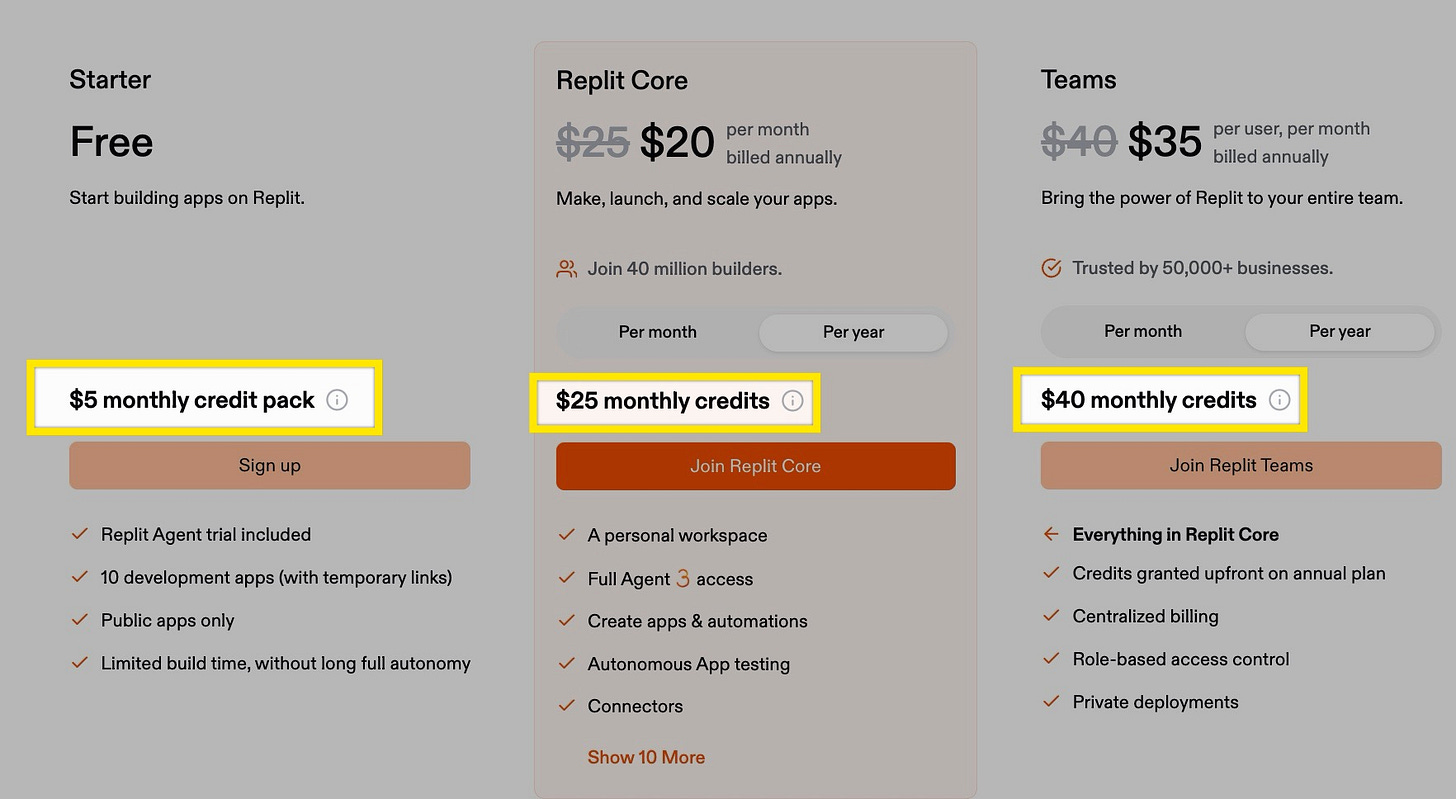

2. Credit-based pricing: Replit

The most common form of AI pricing is a subscription that includes credits. Users pay a subscription which includes usage credits. When they run out, they can top up or wait until credits replenish.

(Technically, the purest form of credit-based pricing is simply selling credits with no regular subscription, but this type of pricing is rare as companies prefer recurring revenue.)

Credits work when users initiate the AI interaction. A product that runs in the background would consume credits without the user knowing.

An example of this is Replit:

Benefits of credit-based pricing:

Fraud prevention: When usage is prepaid, you don’t have to chase unpaid invoices.

Guaranteed revenue: When paired with a subscription, it’s recurring revenue.

No surprise bills: Users know how much they’ll pay, which makes it easier for individual employees to buy.

Margin guarantee: You can calculate how many credits to include to maintain margin.

Account expansion: Top-ups can expand a customer’s revenue.

Downsides of credit-based pricing:

UX Friction: Buying credit packs/top-ups is annoying. Users might restrict usage to save credits and get less out of the product.

Confusion: If you have multiple products or features that consume the same credits, users can get confused.

Intransparent: If credits don’t correspond to user actions, it’s hard to calculate consumption.

Varying margins: Margins become unpredictable because consumption varies between customers.

Unused credits: If credits pile up, users may feel they’re getting a bad deal.

3. Outcome-based pricing

Outcome-based pricing is enabled by AI. It aligns incentives by only charging for successful actions. The most famous example is Intercom’s Fin support agent, which charges $.99 per support ticket resolved.

There are no examples of outcome-based pricing for AI IDEs yet because outcomes have large qualitative spans (A PR could be a new feature or a new button hover effect). If attribution becomes easier, you could imagine outcome-based pricing in narrow use cases.

For instance, you could imagine AI being paid for fixing bugs or finding vulnerabilities—things companies already pay for via bug bounties.

Benefits of outcome-based pricing

Easy to sell: It’s easy to sell a tool that charges you nothing if you don’t make money.

Obvious value: Pricing is directly linked to a measurable benefit.

Downsides of outcome-based pricing

Hard to attribute: In most fields, It’s hard to measure exact outcomes.

Limited application: Most outcomes have too many variables as to be measurable.

4. Subscription with overages

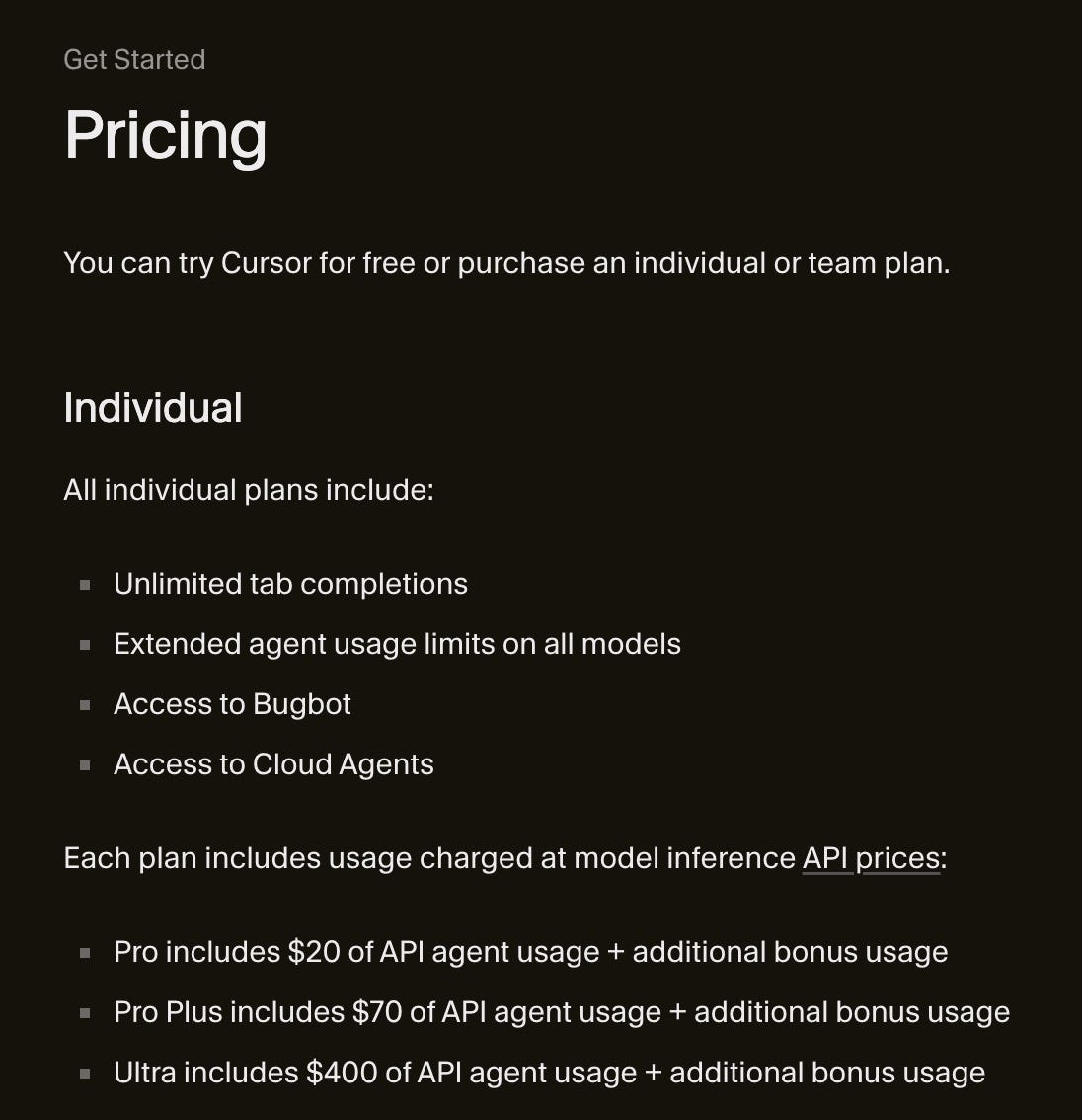

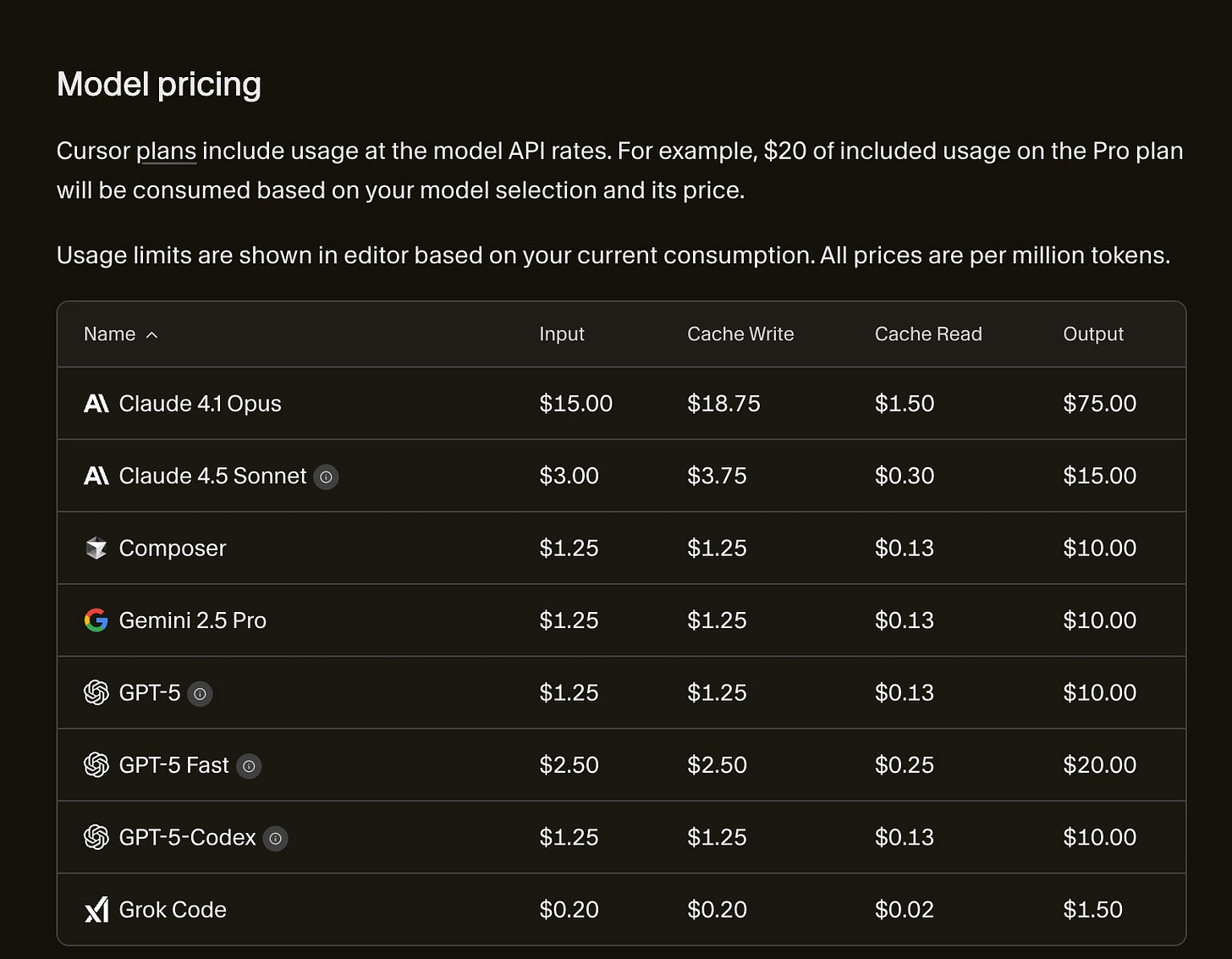

Subscriptions with overages include usage. Once that budget is used up, additional usage is billed on top of the subscription, usually measured in consumption. For example, each Cursor subscription includes a dollar-denominated usage budget. Use it up and you pay for pure usage based on this table:

Benefits of subscriptions with overages

Guaranteed margin: You can’t lose money because you directly bill API usage.

Expansion potential: Your revenue from each customer can grow.

Downsides of subscriptions with overages

Confusing: Customers might get confused by different charges.

Sticker shock: Unaware users could rack up large bills they’re unaware of.

5. Bring your own key (BYOK) pricing

Some AI companies let (or require) customers bring their own API key. This means charging a simple subscription and not monetizing AI usage. This sounds fair, but burdens users with monitoring their spend on another platform.

It works when users are very tech-savvy.

Benefits of bring your own key (BYOK) pricing

Gross margins: Because you don’t pay for AI, your unit economics aren’t threatened by LLM prices.

Fair pricing: You charge no markup, so users view your pricing as fair.

Easy operations: Billing becomes simple because you only charge a simple subscription.

Downsides of bring your own key (BYOK) pricing

No AI monetization: You don’t make money on customers’ AI usage.

Sticker shock: Users could rack up large bills through your product.

Complexity: Many users dislike needing to manage multiple tools.

In practice, most AI IDEs bill some type of hybrid pricing model. They usually combine subscriptions (to make it easy to buy) with a usage budget in the form of credits or dollars (for margin protection).

But whatever model you choose, you need to choose how to measure usage.

Billable metrics in AI coding tools

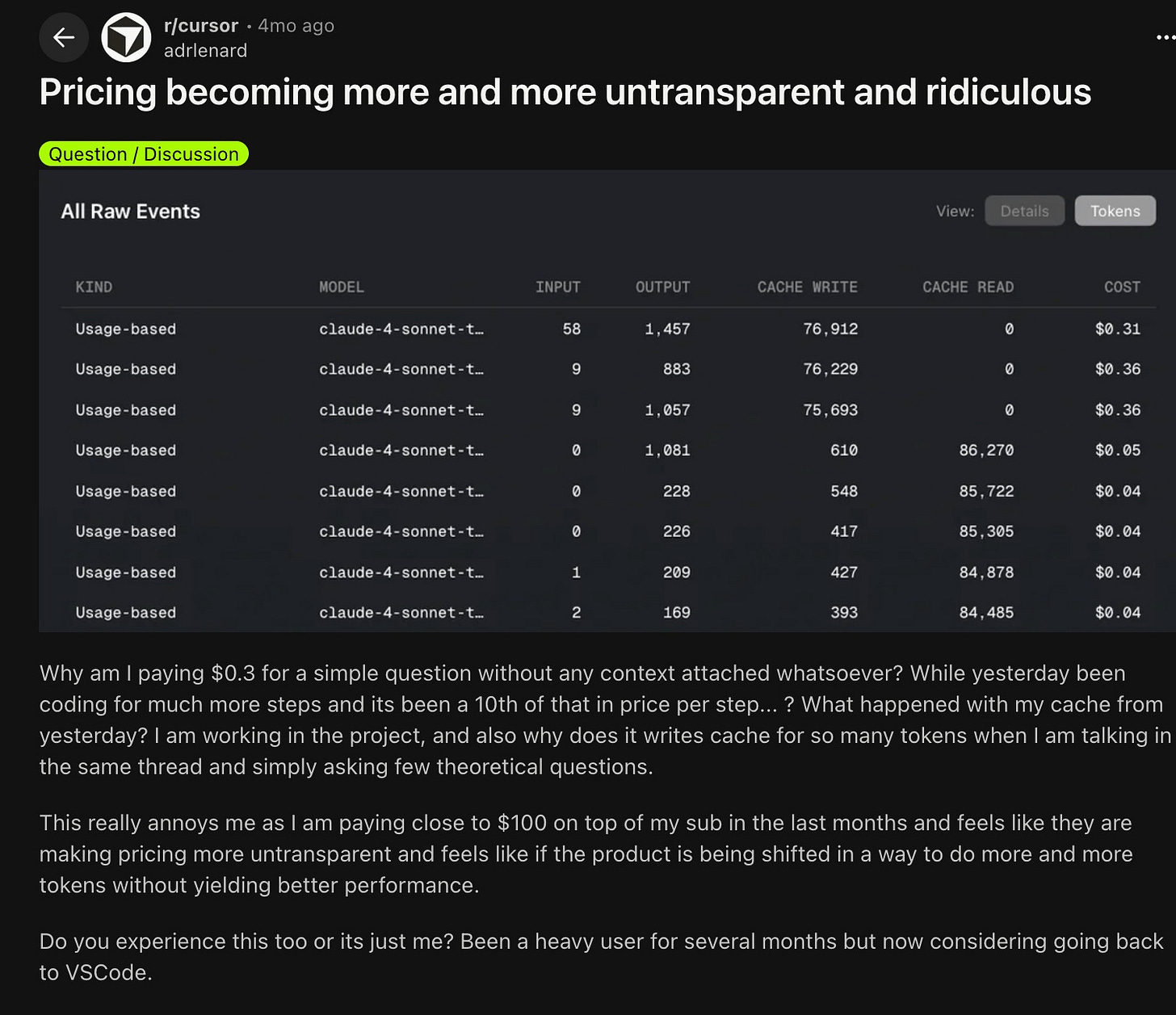

Users think about their usage as “requests” because it’s the action they take. It makes sense for users to bill for them. But as Cursor found out, requests are a dangerous metric. There are two types of variance that make them hard to charge for:

1. Prompt variance

Prompts consume different amounts of tokens. Asking to change a button color to light blue consumes way fewer tokens than asking AI to build a feature from scratch.

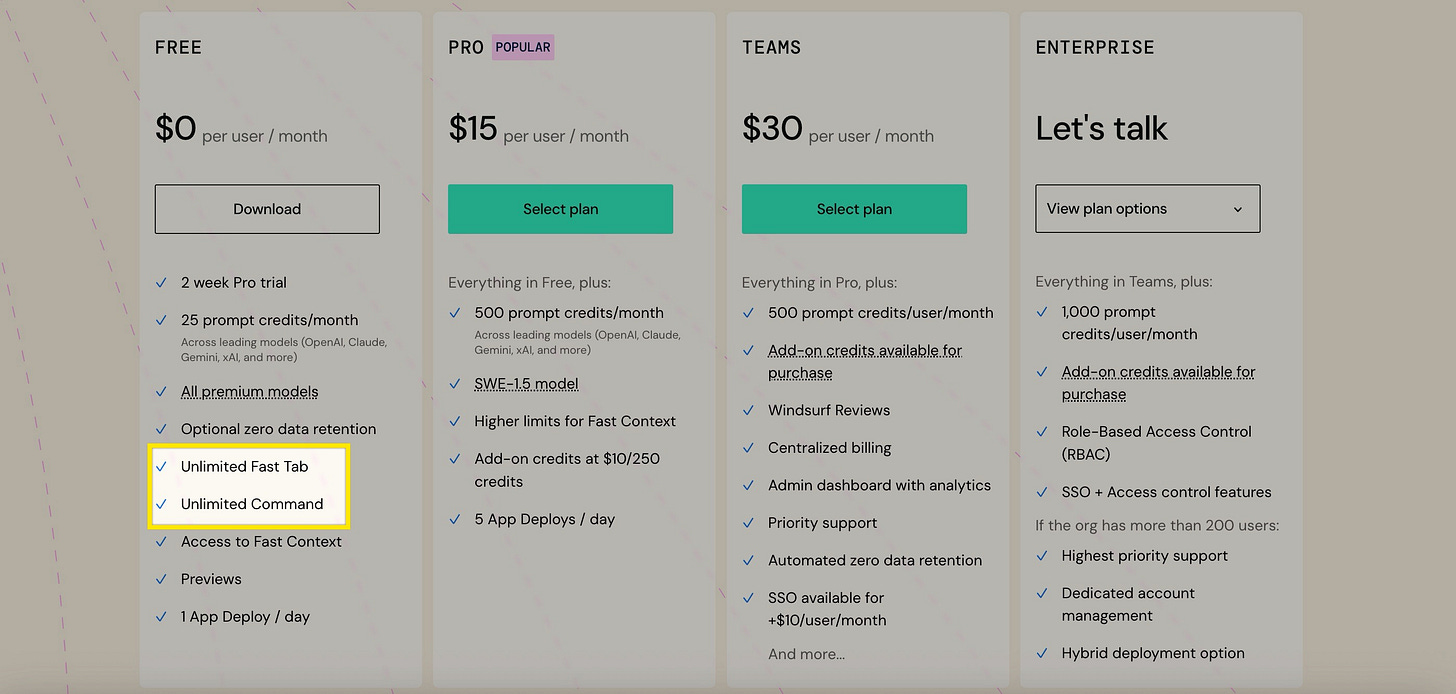

This is why Windsurf offers unlimited Fast Tab and Command: These actions predictably consume few tokens, so it’s possible to offer unlimited.

Meanwhile “prompts” have much bigger variance and thus are rationed more strictly.

2. Model variance

The biggest price difference is between reasoning and non-reasoning models.

Reasoning models generate a “chain of thought” as intermediate steps to the final output. All of those are output tokens! And all of the websites it reads are input tokens!

Even if the token prices of a reasoning model are only moderately higher, the effective price can easily be 10x higher (or even more!).

It’s even worse than that: Users tend to use the most powerful model if given a choice—typically a reasoning model.

This is why Replit and Cursor denominate usage budgets in dollars, despite being less clear to users. When users directly pay for model choice, they’re more economical.

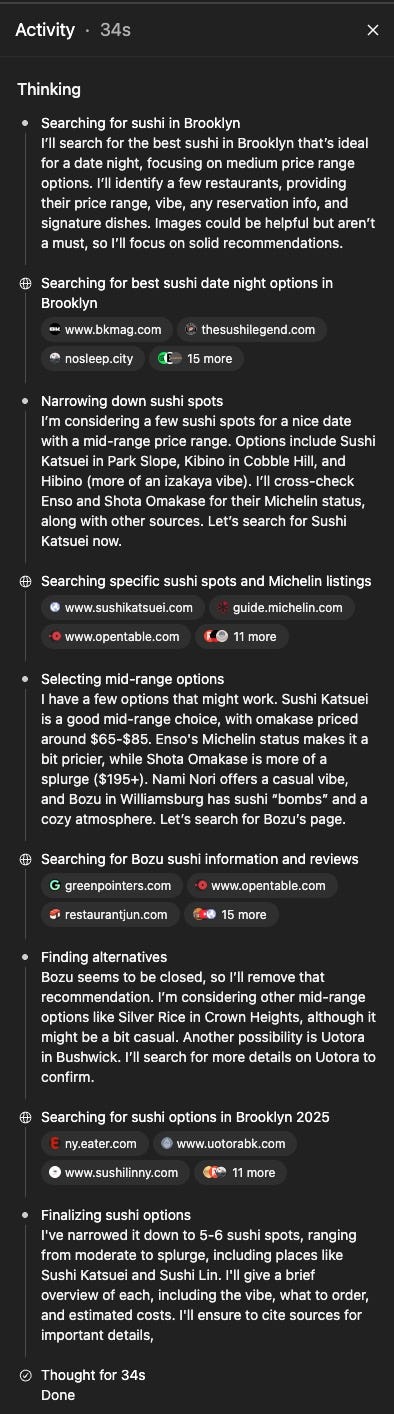

This model dilemma is one ingredient to what made pricing hard for Cursor. But let’s dive more deeply into Cursor and see what they could’ve done better:

Case study: What Cursor got wrong—Pricing AI IDEs

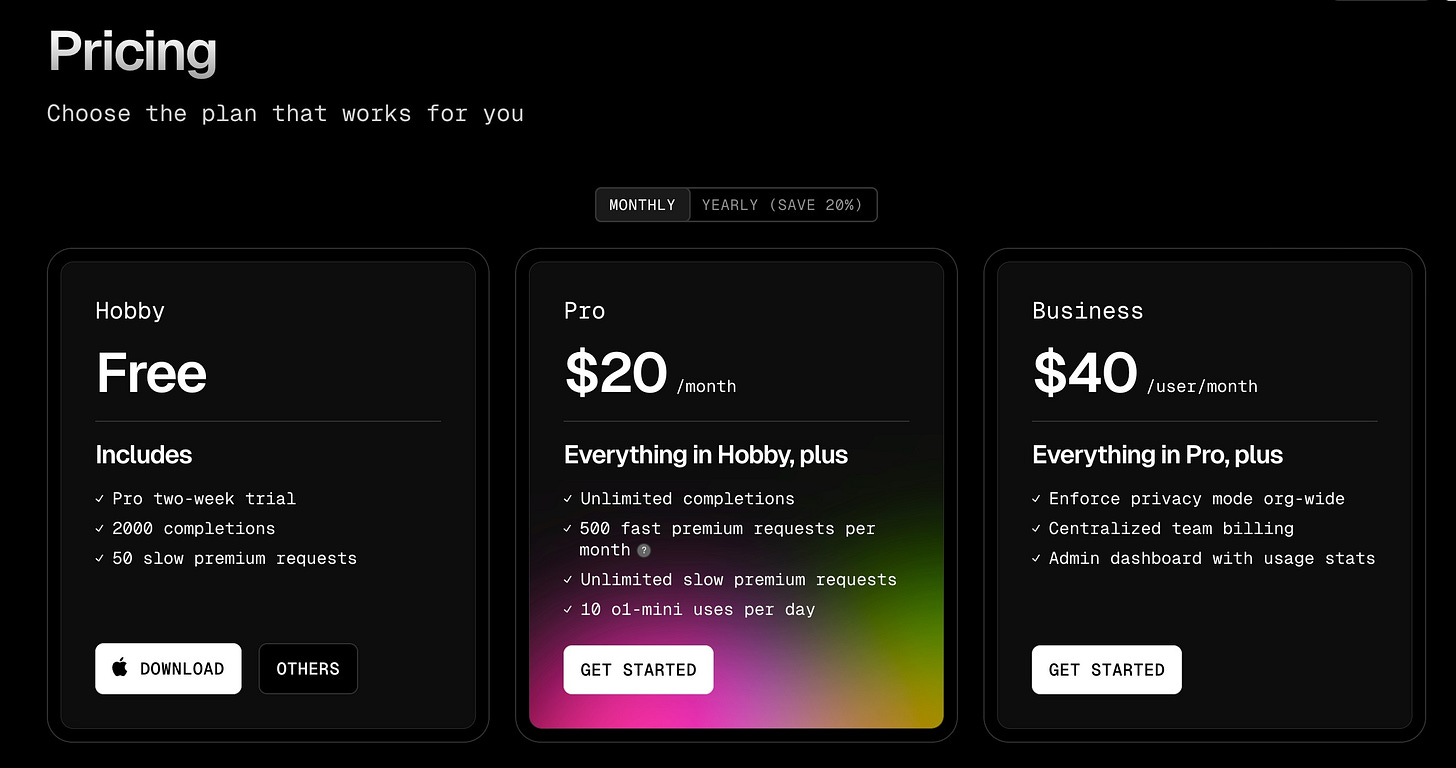

Cursor’s backlash happened when it changed pricing from this:

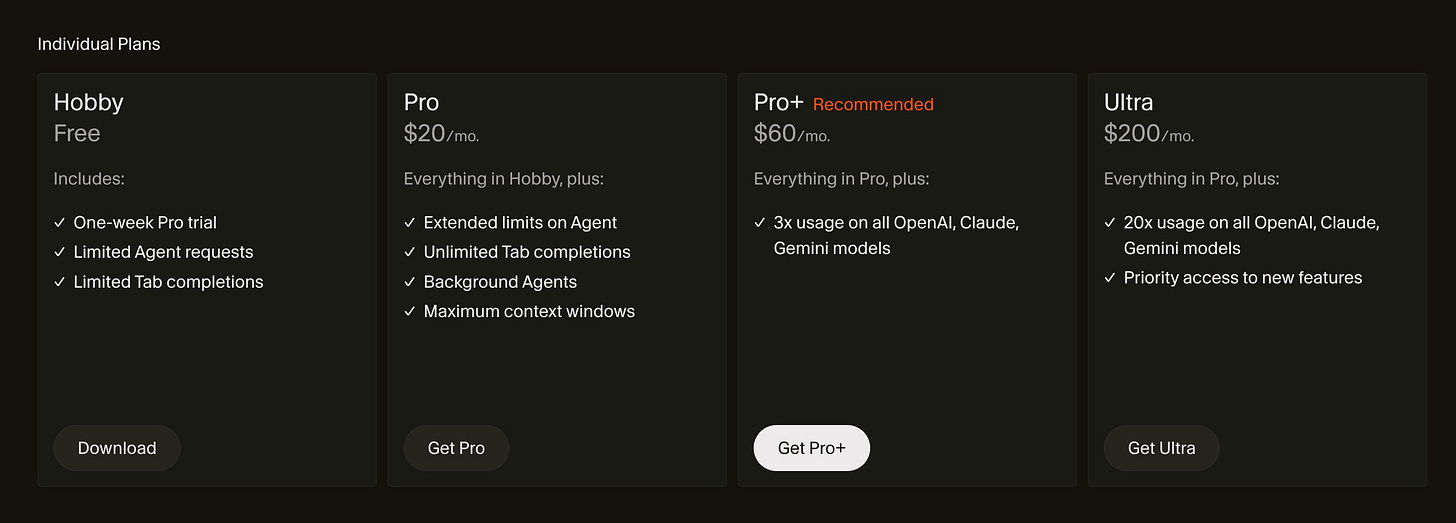

to this:

The main change: Cursor no longer measured “requests”, but measured usage in dollars directly. Its margins couldn’t withstand the cost variance in requests, yet their pricing treated each request the same.

Tweaking the numbers couldn’t have been enough: Assume users only send expensive requests and you need to charge thousands a month. Assume users will be reasonable and you’ll charge too little.

This dynamic reportedly lead AI coding tools to hemorrhage money. Around the same time Cursor changed their pricing, so did Claude Code, Copilot and Windsurf.

Details differed, but they all shared tighter usage limits and more expensive usage. Users hated it. Obviously: You had to pay more for the same result.

When cost control features didn’t give enough transparency, some users also experienced sticker shock at the usage-based invoices.

On the business side, results likely improved. We don’t know the unit economics of Cursor, but this pricing change likely stabilized margins—and probably had another effect: Once users exceed their budget, Cursor earns more than the pure subscription, which pads revenue.

Dollars are an intuitive metric for Cursor’s finance team, but opaque for users. Few users have good intuition as to how many dollars an AI request consumes. There are always tradeoffs.

For an IDE, an engineer’s workspace, reliability matters. So disabling important features because of a usage metric users don’t get is extremely annoying.

Multiple AI coding tools are trying to make their plans feel more unlimited with a few tweaks:

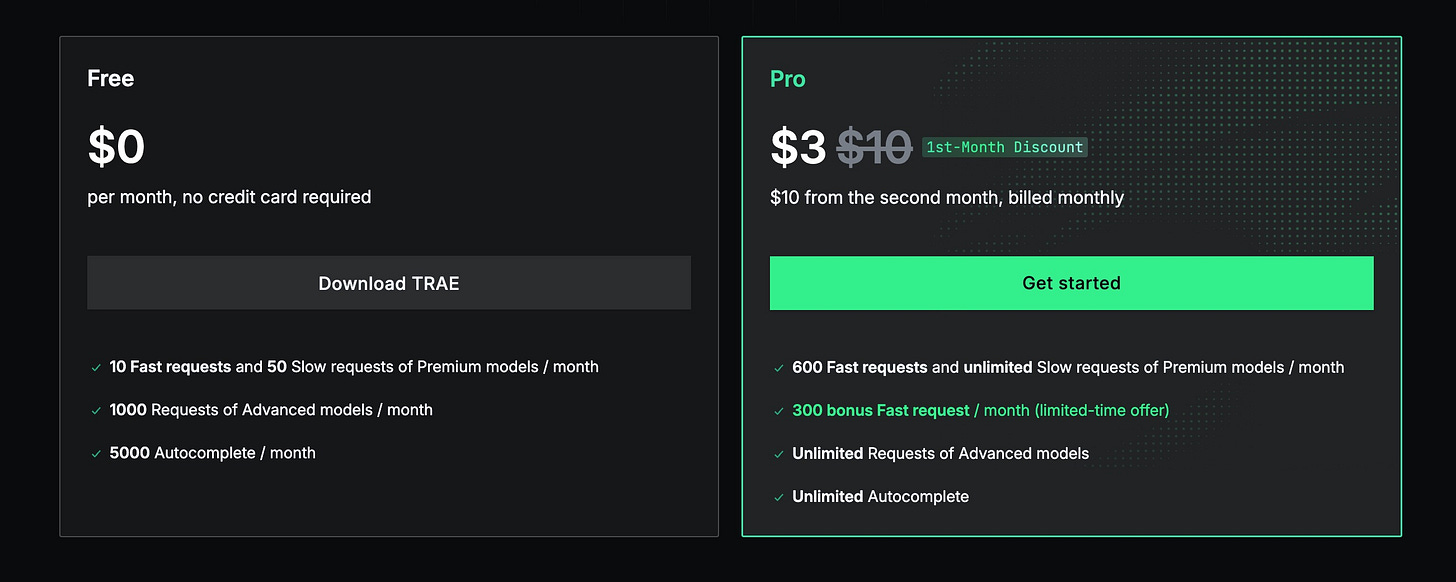

Slow requests

Tools like Trae (an AI coding agent from ByteDance, the owner of TikTok) offer “unlimited slow requests”. This usually means you can make the request, but it’ll take a while to execute. These are cheaper to serve because they use cost-optimized batching, slower infrastructure or wait until compute demand slows and prices drop.

Users get more usage at the same price while costs don’t go up much for the vendor. It makes the subscription feel more unlimited to the user.

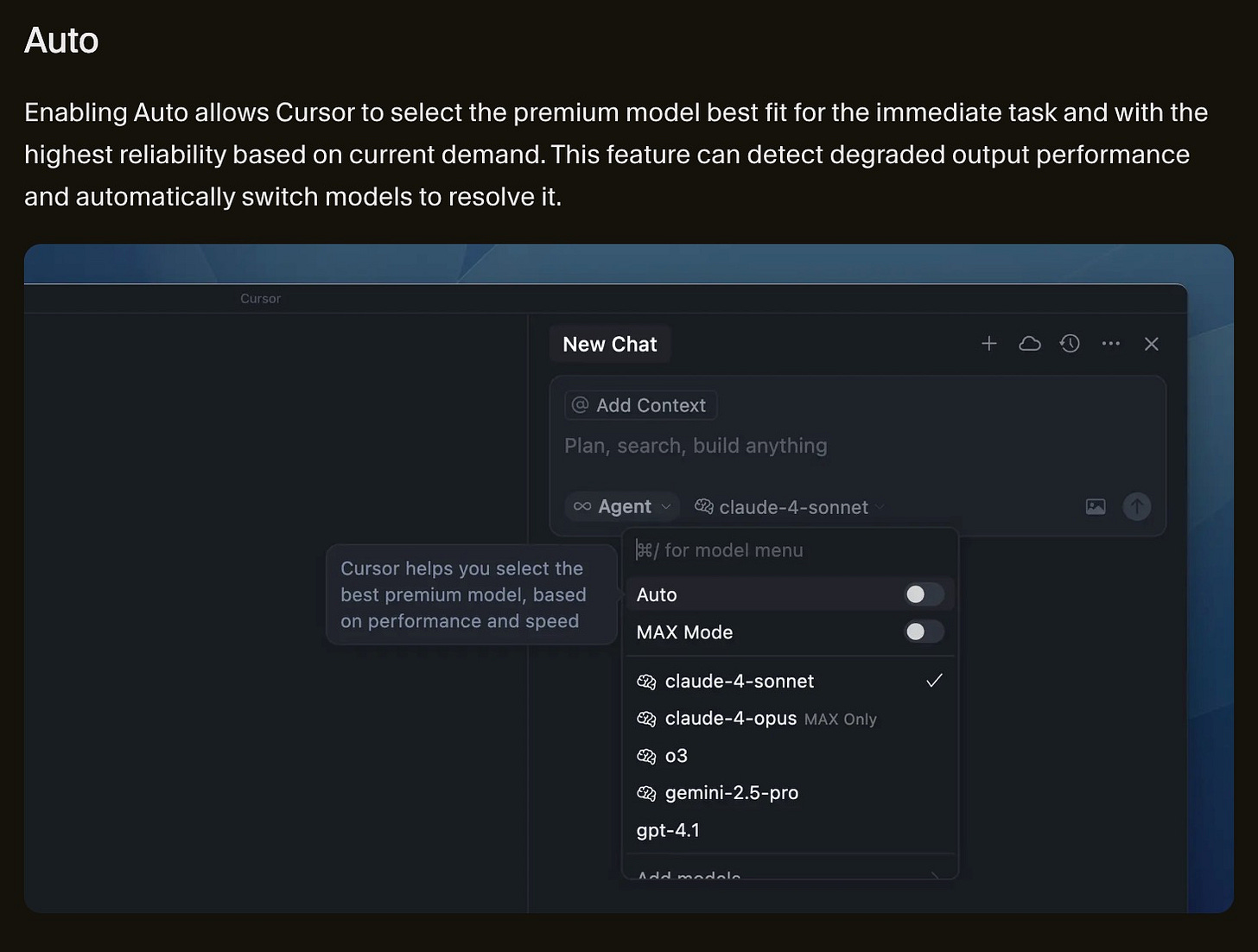

Auto-routing

Cursor offers “auto mode”, which automatically routes each request to a model. Cursor states this lets it route to the most performant model to avoid delays. But it also has another benefit:

Users tend to use the most capable (read: most expensive model) for every single request. But for simpler requests, you can often use cheap, non-reasoning models. Cursor can lower their costs by routing simpler requests to cheaper models.

Conclusion: How to price AI IDEs?

There’s no “right” answer to the question above. This depends on which subset of the market you’re going after, what your long-term strategy is and how you differentiate.

But if you’re going after engineers, you need to be ready for large usage fluctuations and insulate against it. The typical way of going about it is to charge users a subscription fee and bill usage on top of that—whether via credits, overages or bringing their own key.

As always in AI—the only constant is change. But for now, it’s not looking like we’ll find one “correct” pricing strategy for AI. Reforge CEO Brian Balfour mentioned this on a recent podcast episode: “You used to do maybe a pricing change once per year. Now it’s three, four, or even five changes in a relatively short period just to keep up with shifting costs and adoption.”